Energy jobs: Oil and gas industry could hire 100,000 workers – if it can find them

The U.S. oil industry will need to hire tens of thousands of workers in the next two and a half years as oil prices recover and drillers stand up rigs, Goldman Sachs projected in a note this week.

The question is whether workers flushed out of the industry and into a resurgent U.S. labor market will head back to the oil patch. On Friday, government data showed the United States added a whopping 287,000 jobs in June, and the nation’s unemployment rate held below 5 percent.

Recruiters have long warned that layoffs could come back to haunt an industry still dealing with a shortage of mid-career workers following the 1980s oil bust. As the United States reaches full employment, oilfield services companies and drillers could face a shortage of workers and may have to pay dearly for them.

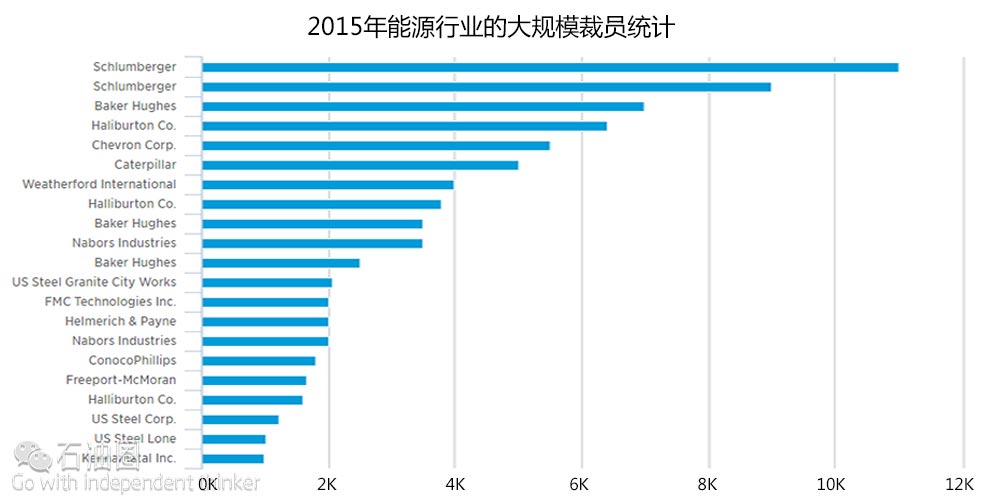

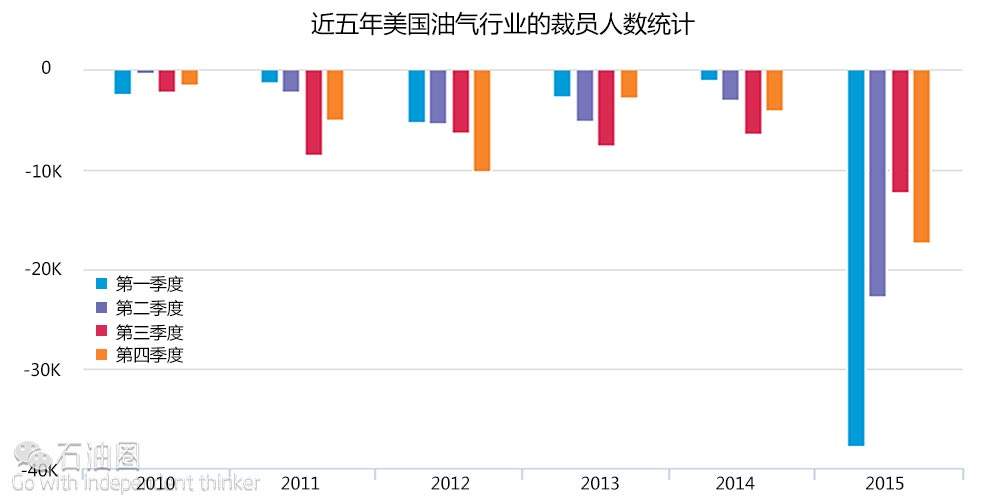

Since the start of the oil price downturn in 2014, more than 291,500 energy jobs have been lost worldwide, estimates recruitment agency Airswift. Airswift Chief Operating Officer Janette Marx said employers should anticipate a significant increase in the cost of attracting and retaining talent once demand for skilled staff returns.

“Job seekers continue to turn to other, related industries that offer more stability. It’s too soon to tell if this talent will exit the oil and gas industry permanently, but if it does, it could result in a long-term, more pronounced talent shortage when the oil price recovers,” Janette Marx, chief operating officer at Airswift, told CNBC in an email.

There are signs the layoffs have peaked. On Thursday, outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas reported U.S.-based energy sector employers cut 42 percent fewer jobs in the second quarter than in the first quarter.

In Goldman’s view, high pay in the oil and gas industry will make it possible for U.S. oilfield services companies to attract the 80,000 to 100,000 employees the bank believes energy firms will need. The industry’s staffing needs would absorb about 8 to 11 percent of the unemployed population in energy-producing states, according to Goldman.

Further, Goldman argues that many oilfield services companies have retained experienced staff throughout the wave of layoffs, and “in many cases” shuffled them into low-ranking positions with an eye toward “promoting” them once oil price recover and activity ramps up. Those staff are ideally positioned to preserve the efficiency gains achieved during the downturn, Goldman notes.

If all goes according to plan, those companies will mostly have to hire and provide training at the lowest skill levels.

But Raymond James believes pay may not be enough to attract workers back to remote oil fields.

“Although these non-oilfield jobs often pay less than those in the oil patch, the stability of employment and less harsh work conditions in non-oilfield industries might offset the lower compensation as the oilfield up-cycle progresses. This is particularly true today after the devastation industry participants have witnessed firsthand over the past 2 years,” the firm said in a note earlier this year.

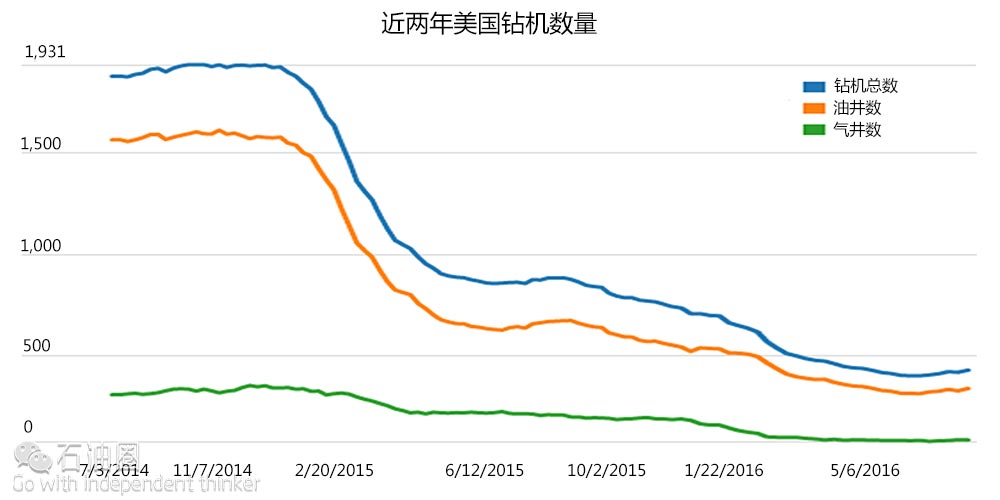

Citing rig operators, Raymond James said the initial addition of 100 to 200 rigs will be manageable, because current staffing can handle the increase. But the firm believes bottlenecks will develop as the U.S. oil and gas rig count approaches 600. It now stands at 431.

Gladney Darroh, president at Houston-based energy recruiting firm Piper-Morgan Associates, is also skeptical that staffing up will be an easy lift. Energy-producing states may have a theoretically sufficient pool of workers to meet the oil and gas industry’s needs, but there’s no telling how many of those workers are qualified and willing to work in the sector, he said.

He also cast doubt on Goldman’s assessment of staffing strategies: “This whole idea that we’ve got this whole group we have sort of demoted for the time being that are still in the organization that we can quickly promote back up, that’s a fairy tale,” he told CNBC.

“These oil services companies don’t even think that way. They slash and burn,” he said. Asked by CNBC for clarification on how widespread a supposed retention-through-demotion strategy may be among energy firms, Goldman Sachs did not respond. Oilfield services firms Schlumberger, Baker Hughes, and Halliburton either did not respond before publication or declined to make an executive available for comment. It’s far more common for service companies to cut to the bone, retain their best workers, and ask those star employees to shoulder a heavier workload until the firm can reverse layoffs, according to Darroh.

But that strategy is fraught, as well, Darroh said. Employers run the risk of overworking their top-performers, who are likely to be pursued by headhunters as resurgent drilling yields labor shortages and bidding wars.

Jeff Bush, president at Denver-based CSI Recruiting, said he already sees signs that this happening, particularly as private equity-backed management teams seek to build out their upstart drilling enterprises. “The directive we get is we don’t want to see guys that are out of work,” he told CNBC. Oil and gas firms will have a tough time meeting their personnel demands as they confront a “three-headed monster,” Bush said.

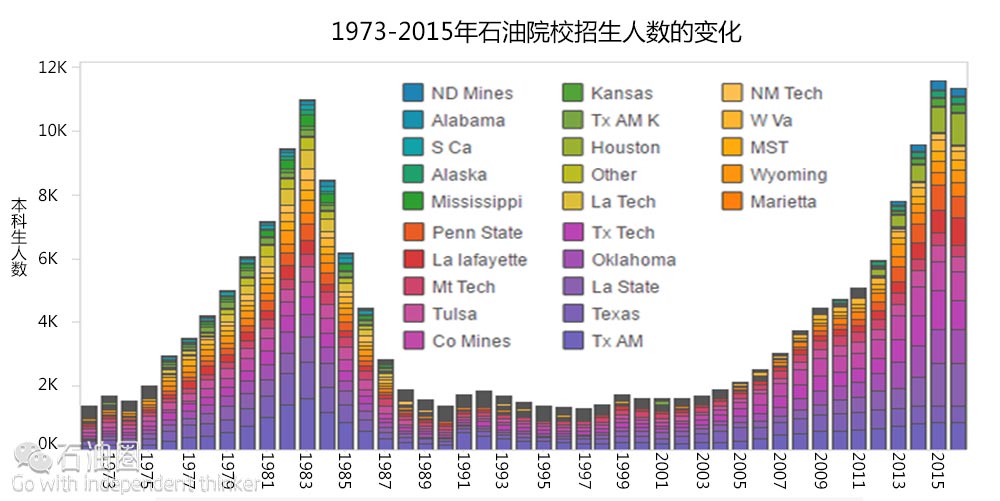

First, the industry hasn’t done any net new hiring in two years. At the same time, enrollment in petroleum engineering degree programs across the United States is falling, department heads tell CNBC.

Lost Generation

Enrollment in U.S. petroleum engineering programs collapsed during the 1980s oil bust, creating a shortage of mid-career professionals. A recovery that dovetailed the U.S. shale revolution is now threatened by a prolonged crude price slump. (SOURCE: Lloyd Heinze, U.S. Association of Petroleum Department Heads)

Second, a number of experienced, high-income workers have retired or been bought out, leaving mid-level workers to fill a skills gap. That potentially exacerbates the long-anticipated staffing crisis known as the “Great Crew Change.”

And finally, some early career professionals without the experience to bide their time as consultants or attract private equity backing have embarked on other career paths.

Ultimately, Bush expects the industry to fall back into its boom-and-bust cycle of hiring. “I don’t see how the industry comes back to any level of activity that is busy without a breakneck amount of chasing bodies, and there just aren’t going to be enough to go around,” he said.

石油圈

石油圈